The person having the greatest Number of votes for President, shall be the President, if such number be a majority of the whole number of Electors appointed; and if no person have such majority, then from the persons having the highest numbers not exceeding three on the list of those voted for as President, the House of Representatives shall choose immediately, by ballot, the President. But in choosing the President, the votes shall be taken by states, the representation from each state having one vote; a quorum for this purpose shall consist of a member or members from two-thirds of the states, and a majority of all the states shall be necessary to a choice. – U.S. Constitution, Amendment XII

There has been an increasing amount of discussion about a possible strong third-party or independent showing in 2016, whether from an independent Republican ticket put up in opposition to Trump, or from a Libertarian or independent campaign capitalizing on popular disgust with the frontrunners for the major-party nominations: Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, both of whom are unlikely to muster approval ratings higher than the low-mid 40s.

This seems like a good opportunity to review one of the lesser-known provisions of that already too-obscure institution: the Electoral College. Under the 12th Amendment, in order to be elected President a candidate must secure an absolute majority (currently 270 votes) in the Electoral College. Thanks to a strange technicality in the way the amendment is written, as little as one Electoral Vote cast for a third-party candidate, could legally result in the House of Representatives electing that candidate President of the United States.

The way it works, is if no candidate receives a 270 vote majority. Then, the newly elected House will have to choose a President, in the brief window in January between when they take office (Jan 3) and Inauguration Day (Jan 20). In this election, they are limited to choosing from among the top three candidates in the Electoral College. Adding an additional wrinkle to the process: each state gets one vote, the only time the House of Representatives votes that way. The delegations from the 43 states having more than one Representative, must vote among themselves, to decide how to cast each state’s one vote. This effectively guarantees that the Republicans would control the outcome of any election thrown to the House, even if they are no longer the majority, because of their dominance in more, smaller states.

The Vice President is elected separately by the Senate (voting as usual), however they are limited to the top two, not three, candidates in the Electoral College.

So, with that basic scheme in mind (see here for CGP Grey’s excellent video explanation): consider the following scenario plays out on Election Night 2016:

The Democratic nominee is Hillary Clinton. The Republican nominee is Donald Trump. The third candidate can be any number of possibilities: Jim Webb, Mike Bloomberg, Mark Cuban, Angus King, or an independent Republican ticket put up in opposition to Trump, such as Mitt Romney or Paul Ryan or Jeb Bush or Marco Rubio. However, since it’s my personal preference, in this scenario we’ll posit that it is Gary Johnson, former Governor of New Mexico, as the Libertarian nominee. The same basic premise can be played out with any of them.

Clinton has 43% of the popular vote. Trump has 39% of the popular vote. Johnson, after being included in the debates on the calculation from both major-party candidates that he would hurt the other more, gets 16% of the popular vote. The remaining 2% scatters to other minor party candidates. (This is roughly similar to the popular vote breakdown from Clinton vs. Bush vs. Perot in 1992.)

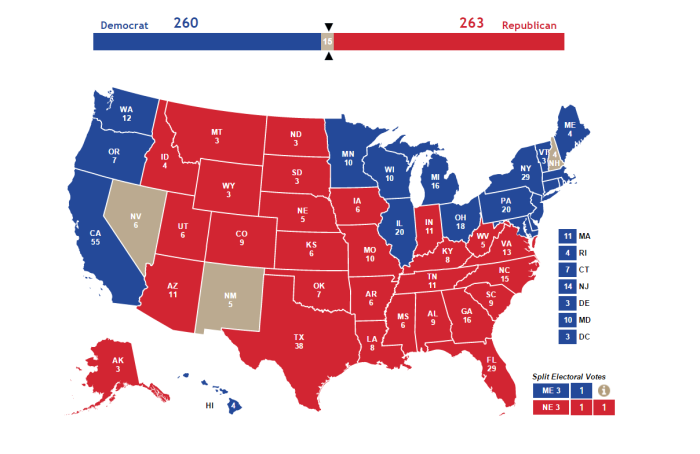

However, the Electoral College tells a different story than 1992. Unlike Ross Perot, Johnson has won a narrow first-place plurality with approx. 34% in three smaller states: New Hampshire, Nevada, and New Mexico, totaling 15 Electoral Votes. The remaining states are near evenly divided: the Democrat ticket has 260 Electoral Votes and, despite being four points behind in the popular vote, the Republican ticket has 263 Electoral Votes.

Instantly, all eyes turn to the House of Representatives, and in particular its Republican members.

The House Republicans are now in a real dilemma. Most have refused to support or endorse Donald Trump’s disastrous campaign, which has continued in much the same manner as his primary campaign, and a small number had even openly endorsed Johnson in the final weeks. Most of those who nominally endorsed Trump, only did so halfheartedly and insincerely.

The Clinton campaign demands that the House confirm her, not along party lines, but because she received, by far, the most popular votes. The same percentage, they note, as Bill Clinton had received to be elected in 1992, though still well short of 50%.

The Trump campaign counters that the voters had returned a GOP-majority House (at least by state), and so the specified process in the Constitution implies that the Republican members of the House should elect their own party’s nominee. Additionally, they count that Trump was the first-place candidate in the Electoral College.

House Republicans are in a catch-22. The vast majority consider Trump ideologically and more importantly, temperamentally, unfit to be President. Many of them have said so publicly. Furthermore, almost two-thirds of voters rejected him, and he lost the popular vote by a wide margin. The idea of a Trump presidency, particularly under these circumstances, with every Republican in Congress to blame, is seen as a nightmare scenario among GOP establishment circles.

On the other hand, few Republican Congressmen can go home to their districts and face a primary, having voted to install Hillary Clinton as President. The massacre in the 2018 mid-term primary elections would be historic, and they know it. They are caught between losing their seats in primaries, or losing their majority in the general election, to voter backlash in favor of the spurned Democrats.

In this scenario, Johnson presents a strongly appealing and compelling dark-horse option. A former Republican Governor with experience in office, and a smaller-government free-market platform, he is much more acceptable to many in Washington than dangerous lunatic Donald Trump. But he also has an appeal and acceptability to the left and center that Trump utterly lacks. The same is likely true of Jim Webb, and possibly Michael Bloomberg.

Facing deadlock and no good options in picking either Clinton or Trump, the House Republicans make an offer: the House will elect the third-party candidate President, and the Senate (still in GOP hands), will elect the Republican nominee for Vice-President. (This is made easier, since the third-place candidate for Vice President is not eligible to be elected by the Senate). This could be Ted Cruz, for example, or another relatively acceptable GOP Governor or Senator placed on the ticket in a failed bid to keep the GOP unified behind Trump. (Alternately, if the Democrats have retaken the Senate, they could independently elect their party’s nominee for Vice President.)

So on December 30, 2016, a press conference is called in the Capitol Rotunda. Speaker Paul Ryan and Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, announce that both of their incoming caucuses had just voted in a special closed-door session, to elect a Libertarian President and a Republican Vice-President. A unity ticket among candidates who, between them, received a majority of both the popular vote and the electoral college. After being sworn in on January 3, the new Congress does exactly that.

And that’s how, if the stars align just right, this obscure provision of the Constitution could allow members of Congress to, in effect, veto both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump and elevate a third-place runner-up to the Oval Office instead.

Far fetched? Absolutely. Impossible? I don’t think so. Unprecedented? Not quite. In 1824, a very similar scenario played out among John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, and Henry Clay. Jackson, seen as unfit despite being the clear popular vote winner, was passed over in favor of popular runner-up Adams, thanks in part to a deal with 4th place candidate and Speaker of the House Henry Clay to appoint him as Secretary of State.

This is not an entirely new idea, either. Throwing an election to the House has long been the goal of third-party Presidential campaigns, most famously those in 1948 and 1968 that swept the Deep South. It is a consideration that should figure heavily into any campaign strategy for a strong third-party presidential campaign.

Pingback: Random Shots for Wednesday, 13 January 2016 | Extropy and Sedition

Pingback: Political fiction must make sense. Does this? – Steve Prestegard.com: The Presteblog

Pingback: Why 2016 Offers a Big Opening for Third Party Presidential Candidate | TheBlaze.com

Pingback: Why 2016 Offers a Big Opening for Third Party Presidential Candidate - Peel the Label

Pingback: Why 2016 Offers a Big Opening for Third Party Presidential Candidate

Pingback: Why 2016 Offers a Big Opening for Third Party Presidential Candidate – USSA News

Pingback: How the Constitution could let the House stop both Clinton and Trump: 12th Amendment 2016? - TKList

Pingback: Could Gary Johnson Be Our Next President? | Western Free Press

Pingback: Could Gary Johnson Be Our Next President? | Drawnlines Politics

Pingback: Podcast 574-Bob Davis Podcasts Radio Show-53